Karissa Chen’s 2014 short story “Altar” begins with what seems to be a reunion of long lost lovers: a man spots a woman sitting on a park bench, realizes she is the woman he loves, and approaches her. The man is observant, a chronicler of detail: he notes her “gold-red hair rising in the breeze. Fair skin pale in the early morning light…her legs crossed…

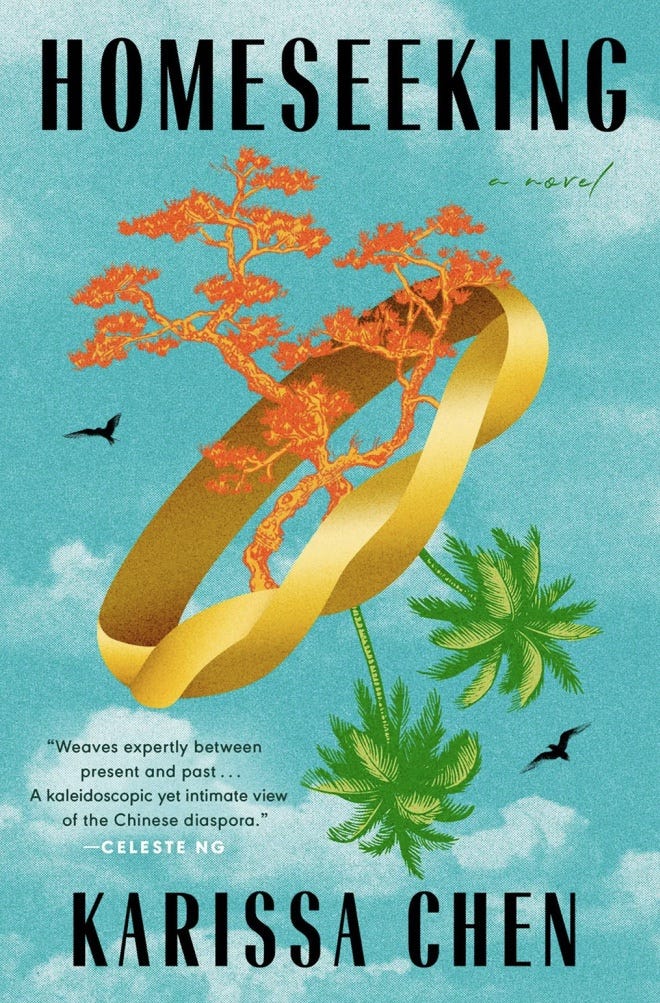

Substack is the home for great culture