On the Nose

Emerging Writer Series

Every two weeks or so I am publishing an essay from an emerging writer. This week, we are publishing “On the Nose” by Muskan Nagpal. Muskan is a writer based in Brooklyn, New York. Originally from India, she studied literature at the University of Delhi and is a graduate of NYU’s MFA in Literary Reportage. Shewrites reportage, essays, and fiction. When not writing, Muskan likes crafting audio stories that make people laugh and cry — ideally in public, with headphones on.

My mother always says, “You are your father’s daughter. Naak pe gussa chadha ke rakhti hai!” Anger sits enthroned on your nose!

I

In her turquoise blue saree, my mother is standing in front of the Taj Mahal. It is a cold, sunlit January day in 2001. I am standing right in front of her, barely reaching her knees. We are in the middle of a circle formed by cameramen. No matter which direction we turn in, there’s cameras pointing at us. These men know we are tourists. Rather impatiently, they are waiting for us to decide which one of them we will choose to get a photo, just for fifty rupees. And then one man takes charge and commands us to pose. I refuse. It is not a withdrawn refusal. I am wailing in anger. I don’t pose for photographs without my father. “He’s just gone for a meeting,” my mother says, trying to placate me. “He’ll come back, we’ll get such a lovely photograph. Come look at that camera over there!” “No!” I scream two times more loudly, and a photograph is taken, despite.

When the English poet Edwin Arnold described the Taj Mahal, he wrote it represents “the proud passions of an emperor’s love wrought in living stones.” It is the tomb of Mumtaz Mahal, third wife to the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan. More colossal than love is the mythology of violence around the Taj. It is a popular urban legend that Shah Jahan chopped off the hands of those who built the Taj Mahal so that there could be no other like it. I am well aware that there is no historical evidence to back this assertion. But sometimes logic has no claim over the pleasures of fancy. The legend means something to me. The Taj Mahal is my first realization that sometimes love lives in cahoots with abrasiveness.

My father, whose name is Vijay, is a tender man except when he is angry. When my father gets angry, then his tongue concedes to brutality. It terrifies me. Seeing him in his bouts of anger makes me forget he loves me.

But then I remember that on some Saturday evenings, he takes me for rides on his motorbike. It’s a silver Royal Enfield that growls. The wind hits my face, and he tells me tales of how time changed his city: the medical college that used to be a jungle, Laddu’s Lentil Shop that has brewed lentils on the same cauldron for so long, it tastes of a masala memory.

Sometime when I was a teenager, I asked my father to let me eat fish pakoras on a Tuesday. On Saturdays, he would call the shop in advance to save some for us. On Tuesdays, he was a devout religious Hindu, which meant eating fish would be the same as asking him to commit blasphemy. At my demand, the anger returned. His voice roared like thunder: “Have you lost your mind?” Every Tuesday he would make it a point to visit the temple. It’s something his father did. In my country, the weight of religious legacy often gets entangled with anger – an emotional echo of control.

In his bout of anger, he went on to question my loose morals, about who was teaching this to me at school and who are these friends I was hanging out with who were asking me to eat non veg on a Tuesday. I tried understanding his sentiments. However, there is something about anger that turns the most familiar person in front of you into a strange specter. Their words gash into your skin, bones, and muscles. When my father screamed at me, it felt like a heavy stone would take shape inside my body and sit there for a long time. It would mold itself into softness as soon as he apologized.

All of which is to say that my father is a typical Indian father. He is fond of his systems of control. Where most modern parents befriend their children, my father believed in hierarchies. I think of this as the schoolmaster problem. Indian schools thrive on administering submission in the name of discipline. When my father and I are arguing, he will often yell at me: “I could never talk to my father the way you talk to me! How dare you answer back?”

II

When I was younger and my father wanted to get me interested in science, he would pull out his Olympus microscope and split petunia flowers under the lens. He always said he loved the way my face changed before and after I looked at them. The fact is that my father has often thought of me as a before-and-after project. When I was a teenager whose skin was pockmarked with acne, for example, he made use of his skills as a dermatologist to experiment with different compositions of retinoic acid and medical salts to render my skin flawless.

My nose, too, has long invited his corrective instincts. When I was just a little baby, he would observe my grandmother squeezing my nose, because she was scared I was going to inherit my father’s—a before-and-after he could not control. Nonetheless, he tried. One day, he took a long look at the offensive organ, and said, “Before we get you married, we’ll get a cosmetic surgery for your nose.”

There isn’t very much wrong with my nose. Like most other noses, it fails to be perfect. Simply put, it is a strong nose which curves in an unflattering hook. Some years after my father’s remark, I attended a medical conference with him. His cosmetologist friends took a look at my nose and instinctively understood what my father meant. They stood around me in a circle, large hands tilted my small pointed face, and then, they contemplated my side profile with a seriousness all too silly – “It’ll take a cosmetic procedure, but it can be fixed!”

I am deeply aware of my nose but I am at ease with it. Others continue to feel differently. “It looks like a mistake on your face,” a friend once remarked. “It’s too rigid.” In the Indian society I grew up in, such a nose is difficult to escape. When my grandmother passed away, a group of old women at her funeral stared hard at me. I had never met them before. “Whose daughter is this one?” they asked “She’s Vijay’s daughter,” my aunt told them. Their immediate response was, “Yes, I thought as much, the nose is definitely ours!”

According to the family mythology, inheriting my father’s nose meant I inherited his anger, his strong-willed opinions, his unmalleability. Perhaps, this could have been true for both our broad foreheads, or our absurdly long fingers. But that happened to be of no interest to anyone. The nose seemed to pronounce the verdict with a finality not very different from the impact my father wanted his words to have. I’ve wondered often, if it’s because a large nose can grant more authority where you have none and a tiny nose can strip away any personality where you have plenty. Or once again, it’s where logic trumps the pleasures of fancy.

Besides, more importantly, I’m not sure if at all I have inherited my father’s sternness along with his nose. We have one too many differences. I approach life with appetite. He is easily satiated with staying home. He is passionately angry. I trick him into thinking I am apathetic. In his world, only one opinion reigns supreme. My opinions are wobblier than Humpty Dumpty on a wall.

Still, a huge portion of my life has passed in an attempt to be an equal with my father. I do this in direct opposition to him. And perhaps in my relentless will to oppose him, I am similar to him—I fight his rigidity with my own. In escaping my father’s nose, my nose ends up looking more like his.

In the January of 2020, I got into a terrible argument with my father. I was working at an art magazine and living in New Delhi. He was at home, a two-and-a-half hour drive away, and I was visiting. He had bought my favorite fruits and sweets: strawberries and rasgullas. I spent most part of the week whiling away time, stealing a treat of fruits and sweets every time I walked past the refrigerator. On Saturday, as his week cleared up, my father offered me a ride in his car. At his age, I was happy about the car replacing the motorbike.

A part of me felt like I had outgrown the drives, but I went along to spend some time with him. During the ride, however, I was completely preoccupied with a wound that had just been inflicted on the country. The government had implemented a pair of policies demanding that India’s Muslim citizens show their proof of citizenship. New Delhi was bursting into protests. My father’s position on the policy was more dangerous than merely supporting it. He didn’t care. This carelessness is what allowed a man of one religion to kill a man of another religion. It is what smothered a democracy into its own collapse. I cared too much. And so, our banter in the car turned into a real conversation.

“Why do you need to be there? What is the need? Sit quietly and stay home, no need to go!” His commanding tone reminded me of the school master. Not only was he telling me how to live my life, he was marking my boundaries. He was ordering me to stay home.

Nothing infuriated me more than my father’s impulse to curtail my freedom in the name of protection. It started with me taking school trips with classmates who weren’t women, controlling the length of my clothes, and here it was, right in front of me, once again. By this time, the drive was over. He was pulling into the parking — which was just an empty spot across an unplastered wall. I got out of the car and slammed the car door louder than necessary. I was keeping the communication going.

When we entered the house, my mother was in the kitchen.

He turned to her and implored, “Samjha isko! Make her understand! You never know what kind of people turn up to these protest sites,” he continued in an undertone, almost as if it was some intimate womanly matter he couldn’t speak to me about loudly. Some Indian fathers are peculiar with this. Daughters they love they love too much; they cannot stand nose to nose against their resistance. And so, my mother feels like a war-torn land between the two of us— always ambushed by our wrath. She sees him because she’s his wife. And she sees me because she was a girl before she was a wife.

But something about resisting the ruling power of your country gives you the authority to resist your father too. This time I slammed the door to my room.

My mother called us for dinner. The table was tense. I told him I will leave at 10:00 a.m. tomorrow. He told my mother he won’t be eating any fruit or sweets after dinner.

“Muskan, why are you so stubborn?” my mother says. “What’s the big deal? Do we ever stop you from doing anything? Just listen to your father, he does so much for you!”

Every time my mother wants me to stop me from doing something, she asks me, “Do we ever stop you from doing anything?” I am a grown woman, and my life can be measured out in curfews. In an undergraduate class, I was taught Jean Jacques-Rosseau’s theory of the social contract. The heart of the matter is this: you give up some of your rights to the State and in return the State looks after you. It seemed to me like the law of our home. In exchange for fish pakoras, strawberries, and rasgullas, my father continuously asked me for obedience. But what happens when the stone sitting inside your body begins to turn? When you love your father too, but ultimately, you are his headstrong daughter?

The next morning he asked if I was going to go to the protests. Students were getting lathi charged. Tear gas shells were thrown to disperse the protests. I was going to go, I told him. When I reached New Delhi, I found out the public train system of the Delhi Metro was not stopping at stops nearest to the protest site. The cab I booked refused to take me all the way to the site upon hearing this news. The driver’s exact words were, “It should be like this only. These leftie types need a lathi to learn some discipline.” I got out, slammed the door and walked off to the protest.

And then, I squinched my nose at him.

III

My association of the nose as a shaper of personality, an index of fate, is not derived entirely from familial folklore. It follows from Indian politics as well. There’s a moment I remember from when I was about eight years old. The table was brought onto my parent’s bed which had a view of the television. A walnut wood square slab, designed for the express purpose of feasting where you’re not supposed to, held a pot of gram flour dumplings in curry, a steel yoghurt and a casserole with light phoolka roti. It was 9 pm in India and time for my father to watch Prime Time News. The television screen was covered with a flurry of headlines. If someone from the other side of the TV were looking at me, the eyes in my head looked like a puppet’s.

“Do you know who won the Cricket World Cup in 1983?” my father asked, trying to quiz me.

I switched to looking at the psychedelic pattern of tacky yellow flowers on the bedsheet, tracing them with my fingers. It looked ugly against the mauve walls in the room. My father was sitting right in front of me, with his legs crossed. The boredom of his taste in questions and television concerned me. I raised my eyebrows and shoulders in sync. My lips frowning. I don’t know. And even if I did, I would react in the exact same way.

My father was imitating me, inflating his face with air. He thought he looked sulky like me, but he looked like a caricature of a balloon with a nose. “Baah, baah, baah”—he was making nagging nasal noises.

Despite his boring tastes, I had to concede him his attempts at hysterics. I knew where he got this from. Even Prime Time News realized it couldn’t be too newsy all the time. Between segments loaded with information, the channel switched to a puppet show called Gustaakhi Maaf (Pardon My Rudeness). These were sculptures that look like a mix of clay and papier mâché agile only with their eyes and arms. Their voices and their noses, their highest point of caricature.

Gustaakhi Maaf

This was when I first understood the connection between noses and personalities. It was all Gustaakhi Maaf’s fault. As a child, I was convinced that anyone with a beak-like nose was vicious. And anyone with a protruding globular nose felt a little dull, destined to doom in politics. Experts on Indian politics have often read a politician by her nose, either as an heir to a dynasty, or sometimes as an “accessory to political ascent.” The first female Prime Minister of India, Indira Gandhi, inherited her father’s—the first Indian Prime Minister’s nose. A political analyst wrote on an Indian news media outlet, “The Nehru-Gandhi Kashmiri nose was (and still remains, to an extent) a potent political symbol… Indira Gandhi’s beak-shaped nose became a constant image throughout her reign as India’s prime minister, symbolising her autocratic ways and dynamic personality.”

Gustaakhi Maaf came to end sometime in 2017. Our country lost its appetite for buffooning our own politicians—and that made a buffoon out of all of us. In its heyday, though, it was all about the noses. “You always had to find the likeness and the exaggeration,” I was told recently by the show’s producer, Richa Sahai. “The audience had to find it funny, but not so much that you lose the real person.” To her, the nose was the most distinct part of the puppet— the only point of differentiation apart from hair, clothes, and the element of voice. According to Sahai, the sculpture artist would often scold her: “All you care about are nostrils and noses!”

When Gustaakhi Maaf stopped airing, Richa said it was because of resistance to humour. But it was also because the country itself had become so absurd that no one could separate satire from reality. Of course, all the aunties I have met in my life have confirmed my beliefs about noses determining our destinies. This is not to say that a political commentator is the same as an aunty, but that they serve the same role—reading power. A girl with a sharp nose is sweet and demure. And someone with a nose that’s small and plump is bound to be amiable, easy to get along with. A large nose with a bump is a shrewd woman in the making. And I? I am just difficult. In a country that fixates over everything, an obsession with noses seems trivial. And yet, it goes on to shape varying versions of reality for me. The nose in India was serious business. And it is a truth universally acknowledged that a man who takes his nose too seriously must do so at the cost of women’s lives.

IV

My father is a funny man but he struggles with my jokes. That’s because whenever I want to cross a boundary that I know won’t sit right with him, I pretend that I was cracking a joke. It’s a tactful method, until some days, depending on his mood, it is not.

When I was 14, we were on a family vacation to a place I don’t even remember. The most distinct memory I have from that trip is the dingy restaurant at the hotel, where the white tablecloth was covered with a plastic sheet. On one end of the room there was a blue-green aquarium with red lights illuminating it. We were sitting in the center of the restaurant and had just come down for dinner. My father was sitting right across from me and I was eyeing my brother for taking sips from my cold coffee. Earlier in the week, my aunt was visiting me and contemplating if she should get a tattoo. I was zoned out on the table and thinking about the different kinds of fluttering butterflies she could place on her body.

“What are you thinking? Finish your food quickly!” my father called me out.

I started taking bites of my naan and malai kofta, and then blurted, “Maybe I should get a tattoo.”

After this statement, I chuckled. With the coterie of cutlery that was spread out between us, my words were perhaps the least dangerous proposition on that table. But something in my father snapped. He made an onomatopoeic thundering sound that announced the arrival of his anger. The weather changed. We were sitting in the middle of the restaurant, and my father was yelling at me. My mother was beginning to get concerned about the gazes we were drawing.

“You say you want to be an IAS officer on one day and then you tell me you want to get a tattoo?” he demanded.

In the Indian imagination, the IAS (Indian Administrative Service) is the most respected government profession. It’s what all Indian middle-class parents in small towns dream of for their children. It means you flirt with power and no one questions you. Largely, it’s a dull job which involves sitting in an office and pretending that you’re changing the world.

All his life, with his endless self-designed quizzes, my father was preparing me to take the IAS examination. He did not have any problem with my ambition. Whenever he thought of my marriage, he thought of a double-income household. And where I grew up in Haryana, in the heart of female infanticide, that’s already a privilege.

Yet my mention of the tattoo touched on something far more troubling to my father than professional ambition—my ability to do with my body what I pleased. To my father, a woman with a tattoo is a promiscuous woman. And god forbid I wield power with my debauchery instead. It would make a caricature of his honor.

In my conversation with Richa Sahai, she confirmed my reading of my life through noses. “When the puppet entered the screen,” she said, “the nose entered first.” It was true that as soon as a woman walked into a room full of strangers, her beauty would open herself to reading. And more often than not, in India, it would begin with the nose. I’ve heard time and again that my nose looks like a pakora.

The nose, however, is not merely an accessory. It’s also the seat of shame. In an older Hindu mythological legend, Lord Ram’s younger brother Lakshman, chops off the nose of a woman that approaches them. She’s Srupnakha, sister to the demon that kidnapped Ram’s wife. It is something the brothers do in jest—perhaps one of the earliest instances of boys will be boys. The story is too entangled. It is ripe with complications. And so, it has opened itself up to interpretations. The writer Amit Chaudhuri, in his story Srupnakha, reimagines the tale. In Chaudhuri’s version, Srupnakha is hitting on Ram. He grows tired of her and tells Lakshman, “Teach her a lesson for being so forward.” As a response, Lakshman chops off her nose. It is largely agreed upon that this is what led to the dramatic Indian saying, “Tumne toh humari naak katwa ke rakh di (You’ve made us feel like someone chopped off our nose).”

It might be true that nobody reads a woman’s shame more arrogantly than other women. But it’s truer that nobody fears a woman’s shame more timidly than men. And my father was aware of that. My body is his integrity. As an IAS officer, I would be a Goddess. As a woman with a tattoo, a vamp. There is not a more brutal blow to a daughter’s heart than realizing that her father, the first man she grows to love, will also be the first man to fail her.

V

My father is also a tender man. On a Sunday afternoon some years ago, he groomed a tree for an hour in his childhood home. Deep within the tree was a nest and two eggs. He wanted to protect the eggs from all the children in the house who were curious to peek inside. I still remember that moment, and him, as still as a chameleon, with changed colors. He was standing in the sun in his striped t-shirt, the dancing komorebi on his face, patiently trimming the leaves. It was hard to tell who was more patient, him or all the green around him. That day in the garden, he wasn’t the only chameleon. The fear in my heart, and all its incarnations, was tinted with pride. I was proud, so proud to be a kind man’s daughter. It reminded me of the time when, as a child, I first sat on a potter’s wheel—he had wrapped his large hands around mine, and before I could crush anything in front of me, he’d said —“not too much force and pressure, gently.”

In the house, my mother teams up with my brother. They’re both aggressive, they take up space. I team up with my father; we let them take up space. Sometimes when we are both sitting in a group of people, we withdraw in similar ways—into ourselves. He’s quiet, controlled and observant. I am calm, daydreamy and zoned out. These are other reasons my mother says I am ultimately my father’s daughter. She has said that when I was a small baby, tiny enough to sit around my father’s neck, I would eat better if he played a game of nosy rubs with me. He would hold me up against his face, coo-coo at me, and sing googly-moogly-mush and then rub my troubling nose against his own.

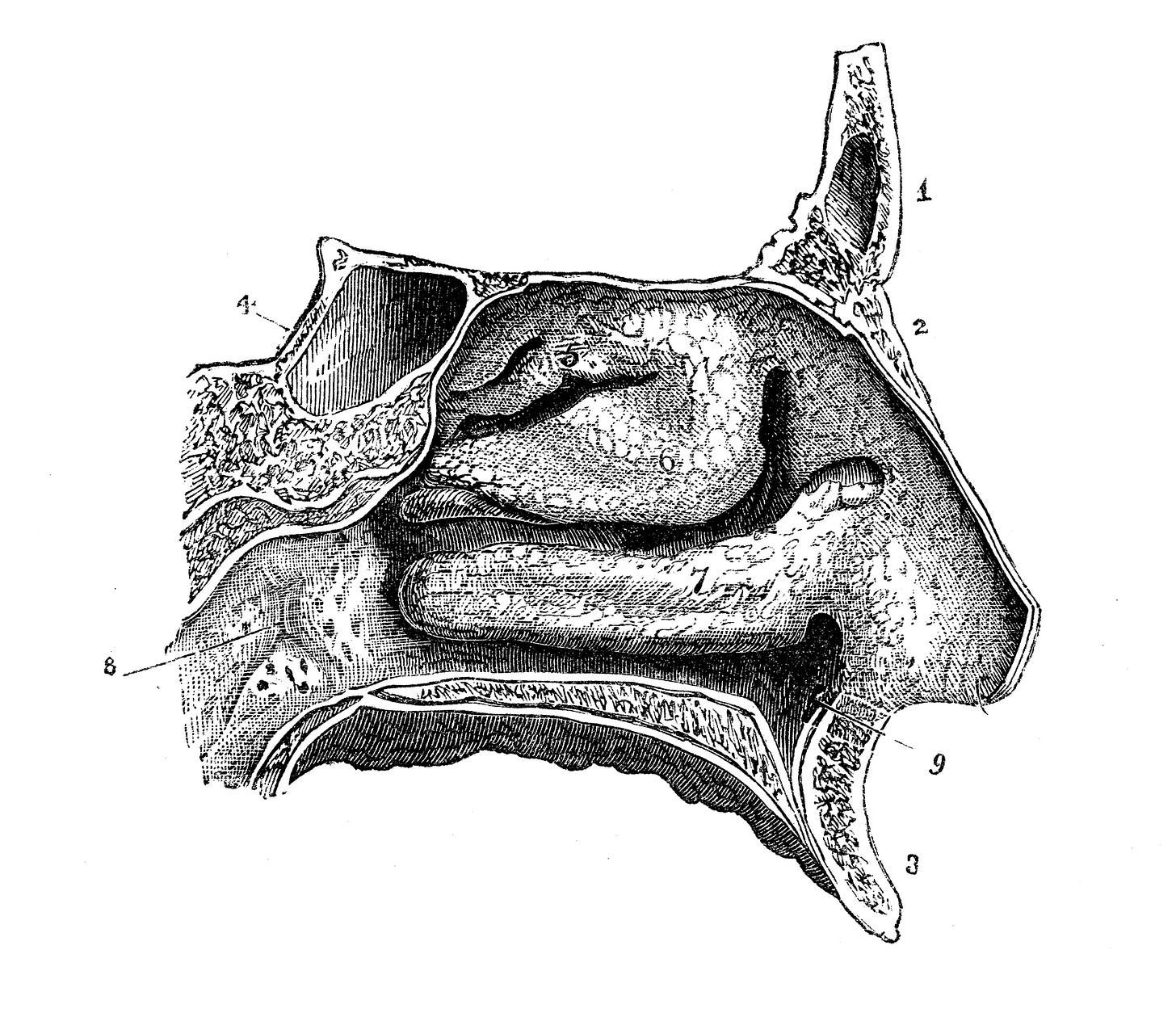

The physiological structure of the nose is such that it is supported by a bone at the back and the cartilage in the front. The bone is rigid, fixed. The cartilage, soft. It supports the movement of the nose so that it keeps its shape while moving. This meeting of structure and agility reminded me of a moment with my father from when I was a teenager. We were at the sangam, or the confluence in Allahabad where the Ganga meets with the Yamuna. The color of the water was distinct – muddy brown for one river and a dazzling blue for the other. We were on the boat, and a net of seagulls hovered over our heads. The setting sun was casting its glow against my father. I could see the silhouette of his nose as he fed the birds—his very effective strategy for control. At some moment, the boatman declared that seagulls can pass on their behavior as inheritance to their baby birds. I looked at my father’s nose and thought of mine. Under the boat, the rivers converged. Under the boat, the rivers also diverged.

Beautiful, Muskan! And that line about anger, rendering someone familiar a specter is soo sooo good.

Wow, this is such a striking braid of tenderness and violence … how love and control can live in the same house, sometimes in the same sentence.

The nose becomes inheritance, projection, shame, politics, myth… and somehow you keep it human all the way through.

That final image of bone and cartilage (structure and softness) and then the rivers converging and diverging… absolutely stunning.